In 2014, I read a news article about the suffering of separated child refugees in Calais whose numbers had risen to nearly a thousand. I found it shameful that just twenty-one miles from the coast of Britain there were children and teenagers living in tents and makeshift shelters in the degrading cold, filth and disease of a refugee camp called ‘The Jungle’ and along the Pas-de-Calais coast.

I started to collect donations of food and essential clothing with the help of other parents at my children’s primary school, teachers and students at the secondary school where I taught – (many of whom were themselves refugees or the children of refugees), and an Ethiopian restaurateur from South London whose teenage daughter had campaigned for period products to be given to women and girls in the French camps. Then I filled my small camper van to the roof and took the Eurotunnel car-train to Calais on a number of occasions.

In Calais, I volunteered with a grassroots French refugee charity, distributing meals and spending time talking to young refugees. Sometimes these were unexpected conversations, like a discussion with a young Iranian about French revolutionary history, and with a young Syrian about Shakespeare’s plays in the camp’s library, ‘Jungle Books’. There was always the obligatory question of which football team you support and kickabouts happening all over the camp, bringing smiles to otherwise down-hearted young people.

I also met many local French people who had resisted the far-right’s propaganda of fear and opened their own flats and homes to refugees to take showers, charge their mobile phones and share family meals.

On one occasion, I met a small thirteen-year-old Eritrean girl in Calais who begged me to take her to England where she had family. Fearing for her safety, I desperately wanted to help her find her family - perhaps smuggling her on the Eurotunnel in one of the many hiding places my children loved in our camper van. I didn’t agree to take her. People-smuggling is against the law; I might have lost my career, been fined and sent to prison. We swapped phone numbers and promised to keep in touch.

In the end, that was the right decision. As I was a known volunteer in Calais, the border authorities strip-searched my camper van as I returned home. My next visit was the last as the French government made it clear that UK aid volunteers were not welcome and were often refused entry.

I am sure that a younger, more impulsive version of myself would not have thought twice about trying to help the girl I met. I often think about her and hope she found her family and safety; not long after we swapped numbers, her phone line went dead.

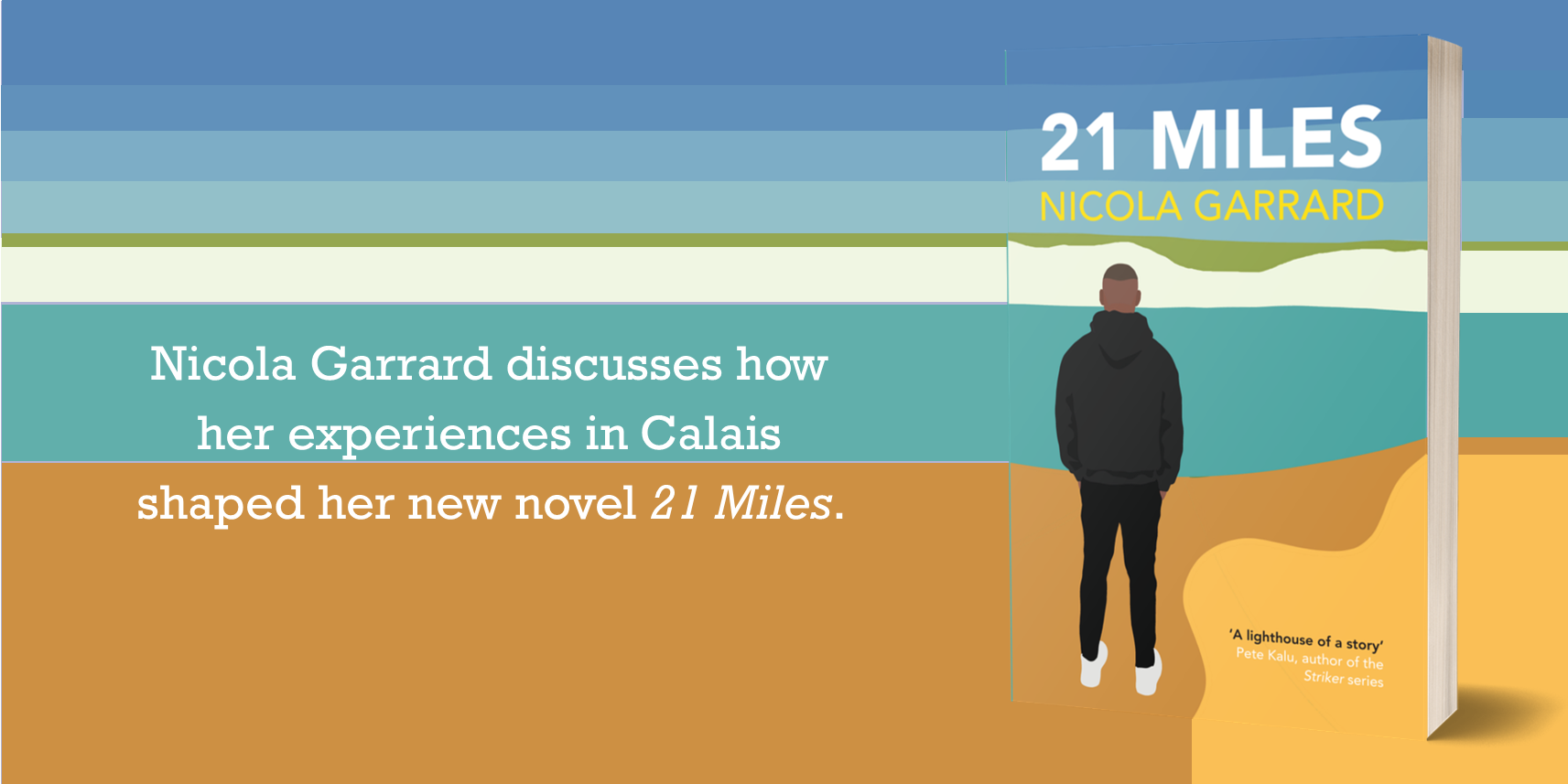

Years later, I was left with the ‘what if’ of her request and it became this story. Since 29 Locks was published, readers often ask me what happens next to Donny. He remained so alive for me that I had been asking myself the same question. I decided to connect these two stories of dislocation, injustice and separation, and see how Donny would respond to meeting the young refugees who had made such an impression on me. Would his bravery, openness and sense of justice make a difference? And what could we learn from teenagers who have travelled across the world to find safety and family?

Nicola Garrard

West Sussex, 2023